The Shapes of Us, Translucent to Your Eye

By Rose Lemberg

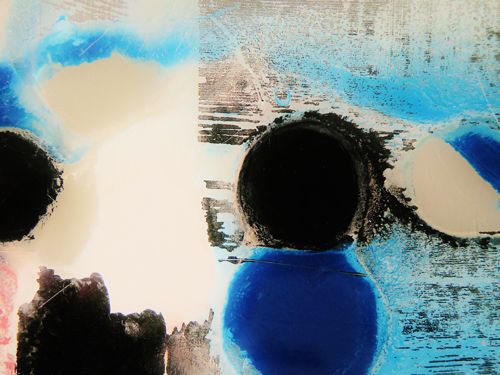

Illustration by Jon Bibire

TCFYC (Translucent Candy From Your Childhood) by Jon Bibire

Fall 2008 is the semester Warda starts at Middlestate U. The tenured faculty members take her aside to impart their wisdom. Your teaching needs to be good enough, but don’t spend too much time on it. Learn to say no to service commitments. Female faculty overteach and serve too much; it takes away from research. Publish, publish, publish — that’s the only thing that matters at tenure time. And, by the way, we are looking forward to your participation in the university-wide Undergraduate Studies committee. No, dear, you cannot say no to that; the department needs a representative. Junior faculty members need to pull their weight.

Spring 2009, she teaches her first Intro to Sociolinguistics. She is delighted to see brown and black faces, as well as white — sometimes it feels to her, at Middlestate, like she is suffocating. But not here, not in this class. There are nineteen kids all counted; they talk about language variants, they talk about standardization. She sees some students breathe out in relief when she says, your Englishes are not wrong or ugly. Mine, neither, she says; immigrant Englishes are neither wrong nor ugly. Some students purse their lips, but she knows by the end of the class they too will get it. There’s nothing truly superior about speaking one variant over the other. Those in power make the rules and police them; those in power call their own speech good and pure, and the rest of us must scramble and aspire.

She comes home and writes about hegemony, while the big oak tree outside her window creaks in unison to her keystrokes.

In Fall 2009, there are tuition hikes. The senior members of the Undergraduate Committee nod — there’s nothing else to cut; hiring is frozen (you’re lucky, Warda, to have been hired with the last wave), and we don’t want to cut our own salaries, do we? Not a word is said, of course, about the upper administrators’ salaries.

They haven’t quite whispered, diversity hire; everybody is oh so polite in her face.

The oak tree creaks outside. Warda writes about hegemony and language and she is one of the lucky ones.

Spring 2010, Intro to Socioling. Sixteen students, but one is not enrolled. He rocks back and forth in his seat, and does not make eye contact. Warda is not sure if he’ll speak up in class. He doesn’t, but afterwards, he stays to talk to her. His name is Arnie. He cannot register, he says, but wants to study this. Wants to be here. Sure, of course, she says, but you’ll need to do all the assignments. I’ll grade them. He comes. Around March, he starts talking in class. They have discussions — about special ed classrooms, about bodies, and how able-bodied people talk to disabled people.

At home, Warda writes about power structures, about defining human; about disability, about the language of erasure. It’s getting harder to find good sources. Her peer review reports come back with requests for more.

The big oak tree outside creaks the spring into summer. She’s placed an article in Language in Society. The senior colleagues are impressed; she’s doing so well, she is assigned to more committees.

Fall 2010, Warda is taken aside by a senior female colleague who’s still an Associate despite her many teaching awards. Don’t repeat my mistakes. Women always do this, women and minorities; but at tenure time, nobody will care how you taught. Just do a passable job, and remember, let nobody audit. The administration is scrutinizing enrollment numbers.

Spring 2011, Intro to Socioling. Sixteen registered, but Arnie’s back, and he’s brought a friend. Lisa is a tall brown girl with a shy smile. Warda lets both of them audit, politely ignoring Arnie’s blurring edges and Lisa’s moments of translucency.

She writes about gender that spring, about gender and power and erasure and pronouns. Especially pronouns. She can no longer stomach the news, does not want to find Lisa’s birth name pop up among murders or suicides — or did she read that last semester?

She trunks the gender paper. There’s so much she does not understand. The authoritative voice escapes her.

Two colleagues are hired away, and replacements are not authorized. She agrees to teach overload in the Fall — times are hard, and everybody needs to pull their weight. But also publish. Publish.

Fall 2012, the undergraduate curriculum is revamped. She clutches her pamphlet with happy glowing student pictures and EMPHASIS ON MARKETABLE SKILLS and tuition assistance. There’s nothing to say. She’s been on the Undergraduate Studies committee for years, but nothing she’s said or written has made it into the final version.

In Spring 2012, the cuts are in full swing. Half of the Intro class is transparent, the students no longer even trying to hide it from her. She asks no questions. She does not like when people ask her — where are you from? Where are you really from? What kind of name is that? These questions inherit the structures of power, the task of deciding what’s central and what is peripheral, what’s normal and what’s strange — she wants no hand in that. She does not want to ask. Died, or expelled, unable to afford tuition — it does not matter. It is enough that in her class, nobody is erased.

What are your publication plans? Warda is silent. She’s helped two enrolled kids from Intro apply for grants; one got the award, but the other’s grant was cancelled at the last minute due to cuts. Both kids, like her, are first-generation college-goers. She spends more weeks researching opportunities, striking out the cancelled ones from her previous year’s list.

Scholarship no longer feels adequate. Warda attempts a poem. Clumsy words cry out into the night and are deleted as the oak outside creaks dissent.

Spring 2013, Intro to Socioling. Hers is the only brown face that is not transparent; the enrolled students loom pale in their seats. There are seven of them. She does her best, but only three are truly interested. They stay after class with the transparent kids, and talk and talk.

They talk of endings — suicides, impossibilities, denials, poverty, and student loans.

The editor of Language in Society wants to see more articles, but she’s unable, frozen; outside her window, the oak’s bare branches hang heavy, unable to bud.

In April, her tenure decision comes through, positive. It feels like a falsehood. The senior colleagues shake her hands and she holds back from screaming, I teach twenty ghost students to seven enrolled. Do you know why? Do you? But she is used to silence by now. She’s one of the lucky ones; most of the members of her PhD cohort are still adjuncting. Those who left are unemployed, overqualified even for clerical jobs. One has gotten a job at Yale, but Warda has never asked if they get any ghost students there.

In Fall 2013, she’s told that Intro to Socioling will be canceled. It simply does not fit the new curriculum — there’s no rubric for it, plus, the enrollments are falling even though you’re such a popular teacher, Warda, and we’re being evaluated solely on the number of enrollments now. Enrollments are dollars, see, Warda—

She assigns her own classroom, an abandoned attic storage space where nobody comes. She posts a few ads — FREE AND NOT IN THE SYSTEM — relying on word of mouth to do its magic. Two days before classes begin, she goes in to check the room, but it has already been tidied; someone has added a wheelchair ramp next to the stairs, and she’s not sure if it’s accessibility services.

Spring 2014, the attic room is full. Transparent kids and non-transparent kids, the kid in the wheelchair, brown black white straight queer cis trans kids, they are there. She does not know if they are enrolled in any other classes. Some are, for sure. Some live in town, others are ghosts that hide inside the walls, waiting for a professor who will not ask questions.

She does not ask questions. She knows she is teaching too many courses again this spring, that she won’t have time to write; she knows it’s not right to abandon her scholarship, that it’s the answer that’s always, always given by those who care, which is why those who care are so rarely in power; she knows this classroom is not a solution either, with so many kids who want to be here unable to come here today — too tired after too many work shifts, unable even to reach the building, not connected in just the right way to find out about the class, left behind or kicked out before they even finished high school — so many. So many. But these kids are here.

She coughs to clear her throat. “This semester, we’ll learn about language in society. We’ll learn about how societal notions — of power, gender, class, race, ability — shape the way we speak, the way we interact with the world…”

Her students scribble. Somebody raises a hand.

![]()

Unlikely Story

Unlikely Story